Booth had steadfastly defended the Confederacy and white supremacy, and his act was part of a larger conspiracy to eliminate the heads of the Union government and keep the Confederate fight going. On April 14, 1865, the Confederate supporter and well-known actor John Wilkes Booth shot Lincoln while he was attending a play, Our American Cousin, at Ford’s Theater in Washington. President Lincoln never saw the final ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment. The first amendment added to the Constitution since 1804, it overturned a centuries-old practice by permanently abolishing slavery.Įxplore a comprehensive collection of documents, images, and ephemera related to Abraham Lincoln on the Library of Congress website. In December 1865, the Thirteenth Amendment was officially ratified and added to the Constitution.

The amendment then made its way to the states, where it swiftly gained the necessary support, including in the South. A proposed constitutional amendment passed the Senate in April 1864, and the House of Representatives concurred in January 1865.

The president, along with the Radical Republicans, made good on this campaign promise in 18. The platform read: “That as slavery was the cause, and now constitutes the strength of this Rebellion, and as it must be, always and everywhere, hostile to the principles of Republican Government, justice and the National safety demand its utter and complete extirpation from the soil of the Republic and that, while we uphold and maintain the acts and proclamations by which the Government, in its own defense, has aimed a deathblow at this gigantic evil, we are in favor, furthermore, of such an amendment to the Constitution, to be made by the people in conformity with its provisions, as shall terminate and forever prohibit the existence of Slavery within the limits of the jurisdiction of the United States.” The platform left no doubt about the intention to abolish slavery. To deal with the remaining uncertainties, the Republican Party made the abolition of slavery a top priority by including the issue in its 1864 party platform. Lincoln understood that no Southern state would have met the criteria of the Wade-Davis Bill, and its passage would simply have delayed the reconstruction of the South.ĭespite the 1863 Emancipation Proclamation, the legal status of slaves and the institution of slavery remained unresolved. The president refused to sign, using the pocket veto (that is, taking no action) to kill the bill. Congress assented to the Wade-Davis Bill, and it went to Lincoln for his signature. Those who could not or would not take the oath would be unable to take part in the future political life of the South. Among other stipulations, the Wade-Davis Bill called for a majority of voters and government officials in Confederate states to take an oath, called the Ironclad Oath, swearing that they had never supported the Confederacy or made war against the United States. In February 1864, two of the Radical Republicans, Ohio senator Benjamin Wade and Maryland representative Henry Winter Davis, answered Lincoln with a proposal of their own. Radical Republicans insisted on harsh terms for the defeated Confederacy and protection for former slaves, going far beyond what the president proposed. These members of Congress, known as Radical Republicans, wanted to remake the South and punish the rebels. However, the proposal instantly drew fire from a larger faction of Republicans in Congress who did not want to deal moderately with the South.

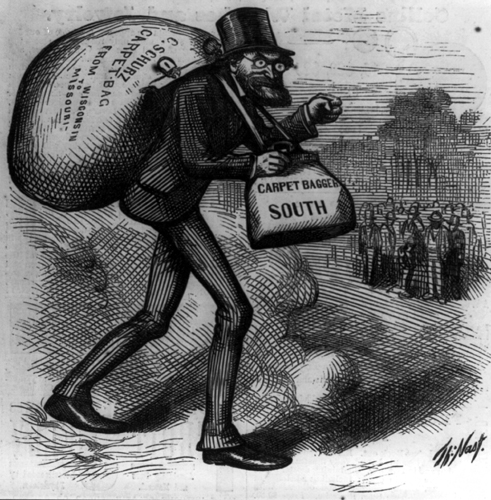

This approach appealed to some in the moderate wing of the Republican Party, which wanted to put the nation on a speedy course toward reconciliation. Lincoln hoped that the leniency of the plan-90 percent of the 1860 voters did not have to swear allegiance to the Union or to emancipation-would bring about a quick and long-anticipated resolution and make emancipation more acceptable everywhere. In this political cartoon from 1865 (b), Lincoln and his vice president, Andrew Johnson, endeavor to sew together the torn pieces of the Union. Le Mere thought a standing pose of Lincoln would be popular. Thomas Le Mere took this albumen silver print (a) of Abraham Lincoln in April 1863.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)